HyperText Transport Protocol (HTTP)

You're HTTPS right now. This book has been delivered to you over a TCP connection using the HTTPS set of protocols. This protocol is the primary protocol that makes the Internet work (alongside TCP/IP.) But what does it do?

HTTP (let's ignore the S for now) is responsible for allowing us to transfer mixed media documents between web servers and web clients. These documents can be made up of text, images, links, videos, WebGL games, audio files, lots more things and everything combined too. It's an extremely flexible way to present data and has grown into the Internet we know today (for good or bad.)

We actually touched on HTTP in the introduction for this chapter on "Protocols". With a simple request we were able to fetch an HTTP response from Google. It wasn't a good response, but it was a response.

When an HTTP connection is made between browser and web server (the remote, server-side of an HTTP connection), HTTP request methods are sent by the client and HTTP status code and returned by the server. This is like a conversation between the two connected nodes. One is asking, "Can I have something?" and the other is replying (possibly), "Yes here's that image you asked for."

Let's review the request methods that a client can send to a remote web server and what they look like.

HTTP Request Methods

In HTTP, you send requests that contain somethings called the "request method". Here's some of the most common request methods (verbs) you'll see throughout your career:

GETHEADPOSTDELETEUPDATE

There are others too, but they can be discovered and read about later on.

These request methods (sometimes called verbs) are used to tell the remote web server what it is you want to do: fetch something, send something, delete something, etc.

But what does the format of a request look

Request Format

Here's the example given by Wikipedia:

Here we can see the three components mentioned: "the case-sensitive request method, a space, the requested URL, another space, the protocol version":

Simple enough. Other information called "headers" can be added to the request as well. We'll cover headers in a bit more detail later on, but essentially all they look like is:

So a key: value configuration. Very simple.

Combined we get this formation:

Which can see as a format structure of:

request-method url protocol-version

header-key: value

header-key: value

header-key: value

header-key: value

Let's look at what a GET is and then we'll look at some common HTTP header types.

GET

This request method is used to get information from the remote web server, and have it transfer from the remote server to the local client. It's like going into a shop and asking for something off of the shelf: "Can you GET that for me, please?" and (a copy of) the item is given to you.

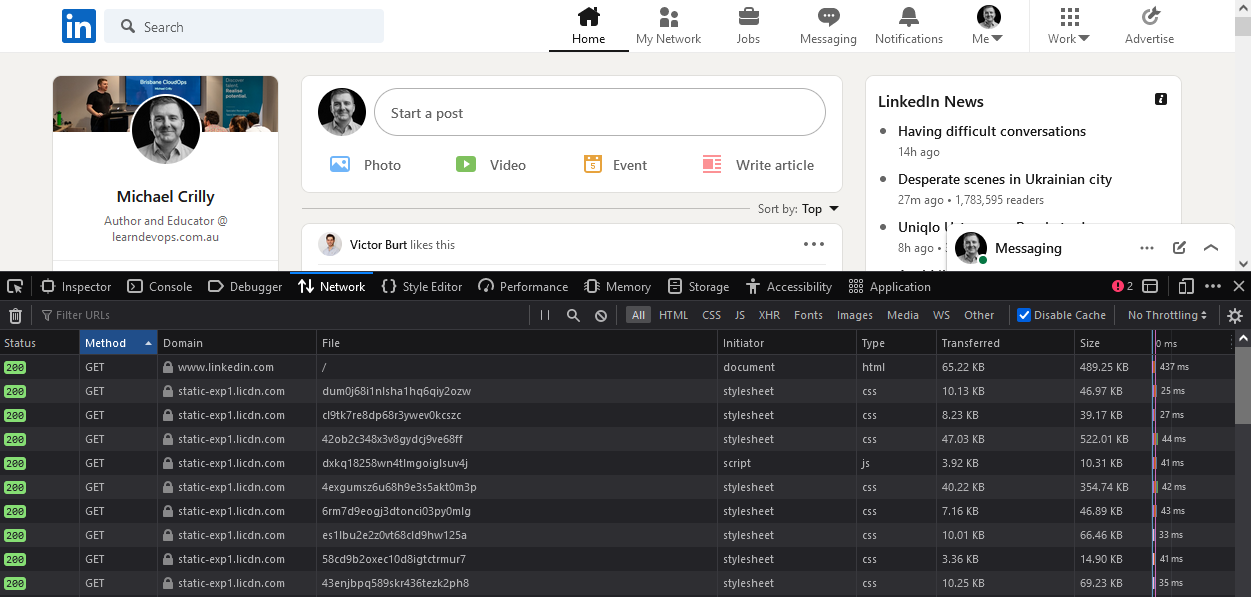

This the most common HTTP request method you'll see. Many, many GET requests are sent to a web server when you first request a website. Here's an example of the GETs sent to linkedin.com after I requested the website in my Firefox browser:

And that's a small amount of the requests that were sent. There are hundreds of them for the one website.

What you need to understand here is a GET is about GETting information from the remote server - asking for some information, state, image, data, etc. to be sent to you, the client.

Note

The HEAD method is like a GET, sort of. Can you discover the difference?

POST

Instead of requesting information from the remote web server, a POST sends it. This is like POSTing a written letter: you package up a bit of information and then you POST it to your recipient.

But what data would you send to a web server? How about uploading an image? What about when you fill in a form on a website to register for a service? These are all POSTed to the remote web server for processing. Let's look at an example of a POST being used to submit a form.

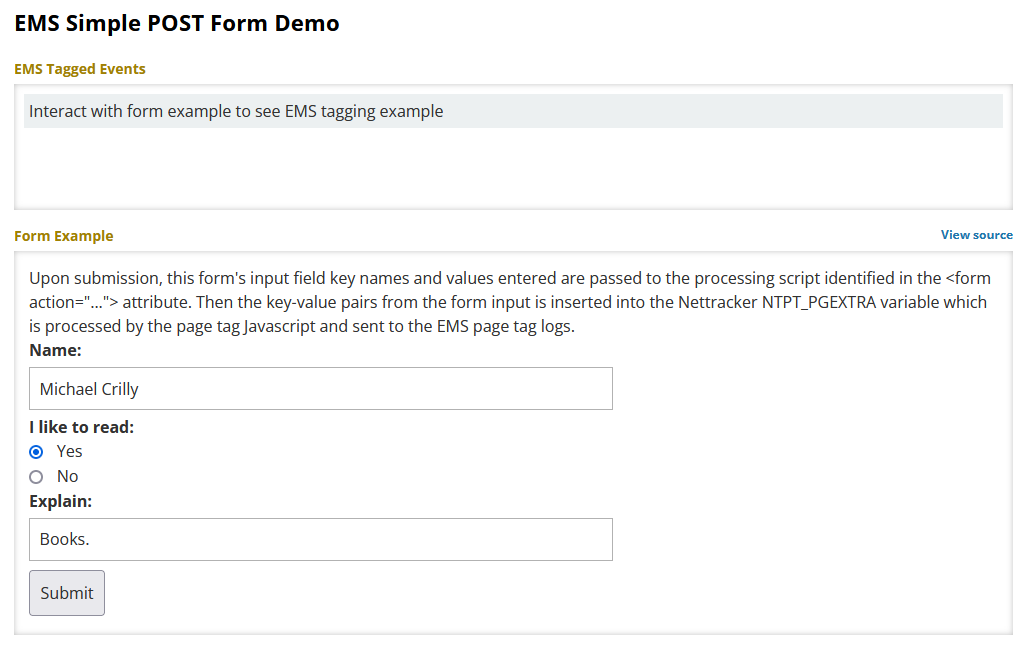

Check out this screenshot from the EMS Simple POST Form Demo. You can follow along, if you like, by visiting the website, loading the developer tools for your browser (Firefox, Chrome), and then filling in and submitting the form. Here's what my form looks like:

First, we can see the GET request my browser sent to the web server:

GET /about/science-system-description/eosdis-components/esdis-metrics-system-ems/examples/post-form HTTP/1.1

Host: earthdata.nasa.gov

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64; rv:98.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/98.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Referer: https://www.google.com/

DNT: 1

Connection: keep-alive

Cookie: f5_cspm=1234

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Sec-Fetch-Dest: document

Sec-Fetch-Mode: navigate

Sec-Fetch-Site: cross-site

Sec-Fetch-User: ?1

Pragma: no-cache

Cache-Control: no-cache

That's a big request compared to what we've seen so far, but don't worry about it. All you're looking at is that HTTP request format we saw earlier: the request at the top followed by the HTTP headers. There are loads of HTTP headers you can send but don't worry about that for now.

All that's important in the above is the GET I'm sending and asking for the form:

GET /about/science-system-description/eosdis-components/esdis-metrics-system-ems/examples/post-form HTTP/1.1

The form is returned to my browser and then rendered so that we can interact with it.

After I click the "Submit" button my web browser reads the form and composes a POST request. It sends it to the remote web server. Here's what it looked like for me:

POST /about/science-system-description/eosdis-components/esdis-metrics-system-ems/examples/post-form HTTP/1.1

Host: earthdata.nasa.gov

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64; rv:98.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/98.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 53

Origin: https://earthdata.nasa.gov

DNT: 1

Connection: keep-alive

Referer: https://earthdata.nasa.gov/about/science-system-description/eosdis-components/esdis-metrics-system-ems/examples/post-form

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Sec-Fetch-Dest: document

Sec-Fetch-Mode: navigate

Sec-Fetch-Site: same-origin

Sec-Fetch-User: ?1

Pragma: no-cache

Cache-Control: no-cache

Inside of the data that was sent I can see this:

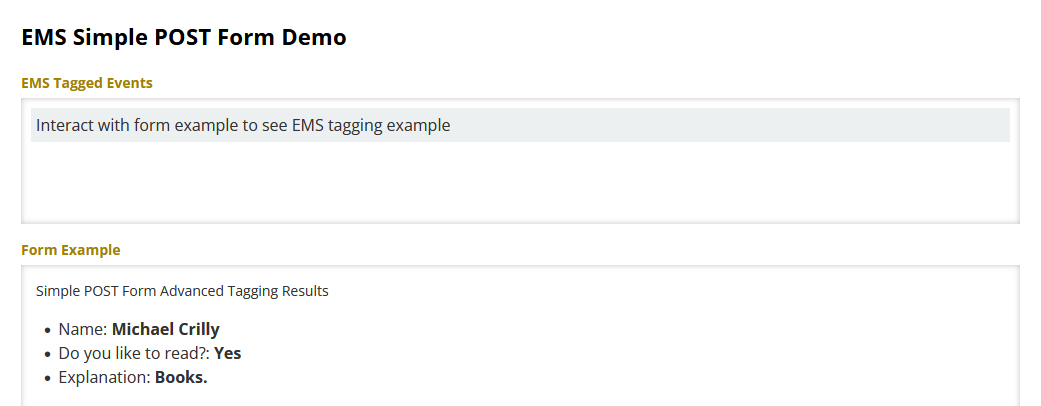

That's the information I put inside of the form: name, read, explain. These are the fields on the form which my web browser read and then packaged into the POST request and sent to the remote web server for processing.

I got a response from the server too:

And that's the basics of a GET and a POST. All this will become a lot clearer when we start building out a simple web server, writing some simple HTML, and fetching the information from the server ourselves using the curl command.

Now we need to talk about are HTTP status codes.

HTTP status codes

So we've fetched information from the remote web server and we've even sent some too. That's been fun to see in action but what if you request something from a web server that doesn't exist? What happens if you ask for a file, say an image, that isn't there?

You get an HTTP 404 Not Found status code.

The HTTP protocol has a lot of status code. Not a crazy amount, but enough that you'll want to only really remember a few of the important ones. That being said here's a link to all of the current codes: https://www.iana.org/assignments/http-status-codes/http-status-codes.txt.

Let's look at a few important notes.

Firstly, look at this part of the above link:

1xx: Informational - Request received, continuing process

2xx: Success - The action was successfully received, understood, and accepted

3xx: Redirection - Further action must be taken in order to complete the request

4xx: Client Error - The request contains bad syntax or cannot be fulfilled

5xx: Server Error - The server failed to fulfill an apparently valid request

HTTP status codes, as you can see, are numbers. They start with (at the time of writing): 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Each are three digits long. The starting digit decides what the code is going to be for, as shown below:

| Status Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

1xx |

Informational - Request received, continuing process |

2xx |

Success - The action was successfully received, understood, and accepted |

3xx |

Redirection - Further action must be taken in order to complete the request |

4xx |

Client Error - The request contains bad syntax or cannot be fulfilled |

5xx |

Server Error - The server failed to fulfill an apparently valid request |

You may already actually know of a very common HTTP Status Code: 404 Not Found.

Here are the most common status codes you'll see:

200 OK301 Moved Permanently302 Found303 See other401 Unauthorised403 Forbidden404 Not Found405 Method Not Allowed("Method" referring, of course, to the HTTP methodGET,POST, etc.)500 Internal Server Error502 Bad Gateway503 Service Unavailable504 Gateway Timeout

All the codes will be around, but they're nowhere near as common as the above codes.

The S in HTTPS

Finally lets briefly talk about the S in HTTPS. It stands for secure and what it means is you're actually using two protocols: HTTP and TLS. We know what HTTP is but we haven't looked at TLS - or Transport Layer Security - yet. We'll cover this in "Basic Security."

In simple terms it means when we're making a connection to remote HTTP (web) server we establish a TCP connection. TCP is a transport layer protocol, because it's responsible for the transport of the HTTP protocol. The problem with plain old TCP is the data is sent over the public Internet as plain text. That means someone between your computer and the remote web server can read the information going between you. That's not ideal for a lot of reasons we'll eventually get into.

To prevent this, we use TLS. In short, TLS establishes a secure TCP connection between client and server. Everything sent is encrypted and cannot be read by someone between you and the remote server. It means we can safely transmit sensitive information to each other over the public Internet. Information like banking requests, private messages, and more.

HTTP/2

What we've used above is HTTP/1.1. A lot of HTTP requests in 2022 are over HTTP/2. Here's the key difference HTTP/2 offers over other versions:

It's way more efficient. Data is essentially "forward loaded" by the web server because it knows the web browser is going to need certain resources before the browser even requests them (because the website authors know what makes up their website, right?)

Encryption is required with HTTP/2 when using a modern browser. The design of the protocol doesn't demand it, but how browser vendors have chosen to implement it means encryption is mandatory, so you cannot access a website over HTTP/2 without TLS.

HTTP/2 is backwards compatible with older versions of HTTP.