Internet Protocol (IP)

If you remember back to when we were talking about TCP and UDP, we spoke about how an application creates some data which is "wrapped" in a TCP packet or a UDP datagram and then sent over the network to another system. What we never covered was how we addressed the data. How did we know where to send things?

That's where IP comes into the picture, and as you already know, we have two types of addresses available: IPv4 and IPv6.

Because we've already covered these two address types in detail, we'll only cover how an IP address is used as part of the IP protocol.

Subnet Masks

When we looked at IPv4 we covered the concept of the CIDR range. This range is used to define the size of a network, and therefore how many usable IP addresses we get inside of it. These subnet masks are used to determine if the IP address you're trying to communicate with is inside or outside of your own network.

Let's say we have two computers: 192.168.1.10/24 (our address) and 192.168.2.30/24. Because we know a /24 gives us 254 usable address, we know that 192.168.1 and 192.168.2 are different networks. We also know this because the /24 means the network is made up of the first three octets in the address.

If we want to talk to 192.168.2.30/24 from our address our operating system knows this is outside of our network. So what happens?

The kernel sends the data to the "default gateway", which is common way of saying: to the router.

Default Gateway

In almost every case, the very first address inside of a subnet is used for and held by the default gateway - which is usually a router. In our example the routers would likely be 192.168.1.1 and 192.168.2.1.

That means that when we try to talk to 192.168.2.30/24, the data is sent to 192.168.1.1, which in turn then routes it to 192.168.2.1 (unless that same router is also in charge of the network, then it just routes the traffic directly to 192.168.2.30.)

This is how hosts on two different networks can talk to each other.

The Route Table

Operating systems store information about the network around them inside a "route table". Network routers also have this table too and it'll look slightly different for them.

This route table contains everything your host computers needs to know to send information from itself to other hosts. Here's an example route table:

| Network Destination | Netmask | Gateway | Interface |

|---|---|---|---|

0.0.0.0 |

0.0.0.0 |

192.168.1.1 |

192.168.1.10 |

127.0.0.1 |

255.0.0.0 |

127.0.0.1 |

127.0.0.1 |

192.168.2.0 |

255.255.255.0 |

192.168.1.1 |

192.168.1.10 |

In this table we're defining the rules for moving traffic between networks.

The most interesting of these rules, and one you'll see often, is the 0.0.0.0 rule. It's commonly seen written as 0.0.0.0/0. This rule catches all traffic that doesn't match the other rules. This is how you're able to talk to the Internet, because 8.8.8.8/32 doesn't match any other rule, so the data is sent to the default gateway which then decides how-to get your traffic to 8.8.8.8/32.

We have our localhost in there too: 127.0.0.1. This is called the "loopback device" and it refers to your own host. This cannot be routed outside of your own system.

Finally, we have a rule for the other network 192.168.2.0/24 (255.255.255.0 is another way of saying /24, remember). Technically not required as 0.0.0.0/0 would catch this, but for our purposes it demonstrates a point.

Header

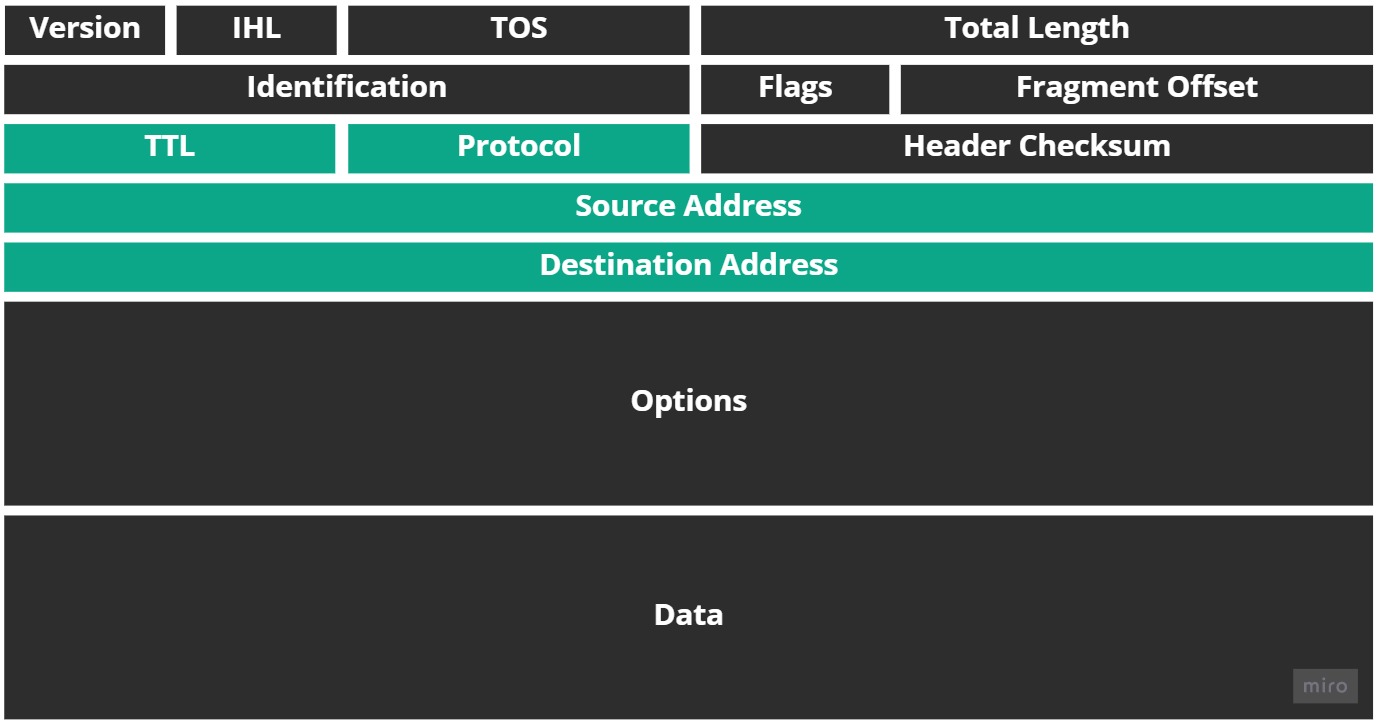

As with TCP and UDP, the IP protocol also has a header:

I've very rarely looked at headers of either TCP, UDP, or IP in my career. It's just not required at the public Cloud level. Still the only headers of note here are the: source and destination address, TTL and protocol.

The source and destination headers contain the address of where the packet is coming from and where it's destined to arrive at.

The TTL, or Time To Live, is how many routers (called "hops") the IP packet can try to traverse through before all routing efforts are stopped (this is how ICMP/ping works, which we cover next.)

And the protocol field is used to contain the protocol - like TCP or UDP - that the IP packet encapsulates.