Transport Control Protocol (TCP)

TCP is a system for managing parcels of information called "packets". Packets are containers you put information inside of and send off to another system on a network. This system of managing packets that we call TCP comes with guarantees like reliability, re-sending if the parcel doesn't make it, error checking to make sure the parcel is in its original state and hasn't got corrupted along the way, and more. TCP sends and works with packets of information.

It's important that you understand one key point here: TCP is used to send multiple packets of data, but it's not responsible for deciding what that data is. It's simply the courier of the data, not the creator of the data.

Think of your local postal system. You write a letter (the data) to someone and then you go to the post office. You hand them the letter and tell them the name of the person you're sending the letter to (the address, which is where IP comes in later on). They put the letter (the data) in an envelope (a packet), which they are responsible for, and then offer guarantees about the delivery of the envelope (packet) to the person you wrote the letter (data) for. They even check the person signs for the letter and then send you back a confirmation of delivery.

So TCP is the postal system but the application, like Firefox, is the author of the letter that gets put inside the packet and sent using TCP. Or put another way:

"The Transmission Control Protocol [TCP] provides a communication service at an intermediate level between an application program and the Internet Protocol [IP]." - Wikipedia (edited by me to highlight certain words)

It's the kernel's job to handle the TCP(/IP) stack.

TCP is used for pretty much all Internet communications you've ever used. The most common applications like browsing the Internet, email, remotely administrating systems (something we'll do later on), transferring files, etc., are all done over TCP (and UDP.) It's an extremely powerful protocol.

Client/Server Model

Typically, the software you're running on your local system, such as a web browser like Firefox, is called a client. The client makes connections from your local system to remote systems to request information. In the case of Firefox that connection is set up using TCP and is then used to request web sites.

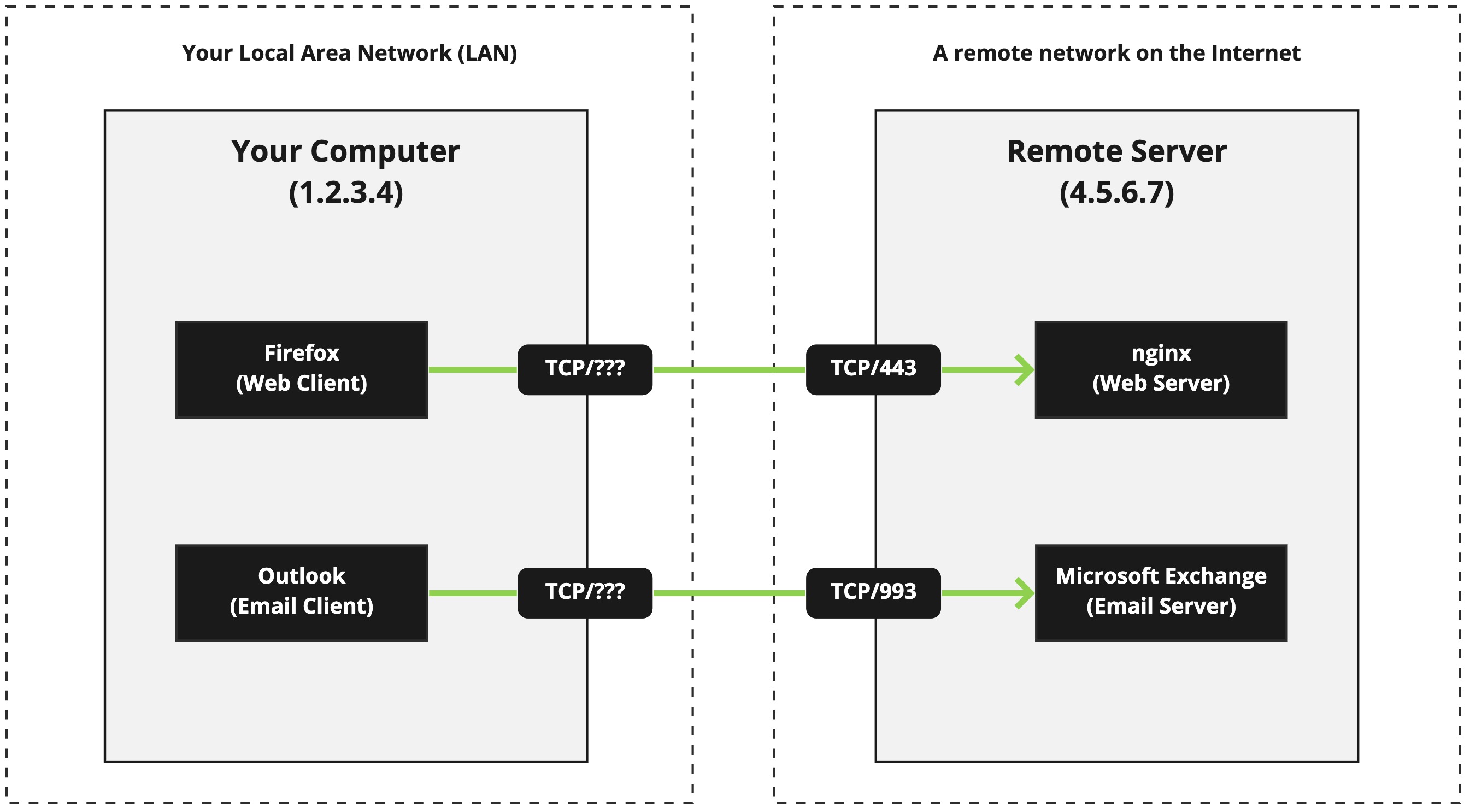

Visually, the client/server model is very simple, but there are some key bits of information you need to know about today so you can understand the more complex networking (security) concepts later on.

Here's what the client/server model looks like, along with those extra little details:

So what are the details we're interested in? There are four (4) pieces of information that are important in a client/server connection:

- The client's IP address (

1.2.3.4) - The client's port number (

???) - The server's IP address (

4.5.6.7) - The server's port number (

443or993)

Three (3) pieces of this information are known to us, but the ??? is an unknown piece of information. That's because on the client's side of the connection there is also a port number. That port number is used for traffic that is returning to the client after the server has something to send it. Without a port number on the client side, the server wouldn't know where to send the data the client originally requested.

This client-side port number isn't really known because it can come from a huge range of ports, and even the range of ports is truly fixed in place - it can change based on the platform the client is on (Windows, macOS, Linux, etc.) The remote server is, of course, given the information in the TCP headers, but there are circumstances when we don't know the port number.

This isn't some mystery or problem we have to solve as engineers, but as you'll see much (much) later on in the AWS section of this course, it does introduce problems as we can't really know the port number and as such, we cannot design network security policies to be perfect.

That's all we really need to know about the client/server model at this point in time.

The Handshake

When two computers want to talk to each other (the client and the server), and they know to use TCP ahead of time, they establish a connection using a three-way handshake. It goes a little something like this:

SYN: The client sends aSYNTCP packet to the serverSYN-ACK: In response, the server replies with aSYN-ACKTCP packetACK: Finally, the client sends anACKTCP packet back to the server

There are three steps, which is why it's called the three-way handshake.

Port Numbers

I have a question for you: what happens if you have two TCP services running on one computer and you want to talk to one of them? How does the client/server model know what service you want to connect to? That's where port numbers come into play.

With TCP (and UDP, which we cover later), a port number is used to identify what service you want to talk to on the remote server. Let's look at an example.

When you request https://upload.academy in your web browser, it knows you want to connect a remote system with the hostname upload.academy (covered in DNS) via the protocol HTTPS (explained later.) So the remote server is using the HTTPS protocol to communicate with clients (your browser.)

Because HTTPS is a known protocol, your browser knows two things:

- It needs to connect using

TCP; - It needs to connect to port

443;

A service like HTTPS listens on a particular port - 443 - for new, inbound TCP connections. This is also called a "socket." So the webserver software creates a socket that is bound to port 443 using the TCP protocol. Once the connection is complete, the browser then uses the protocol HTTPS to "talk" to the remote system. We covered this conversation in the overview of protocols.

Your browser will also use a "socket", locally, when communicating with the web server at upload.academy, but the port number will be random. Unlike the web server which needs to listen on a fixed, known port (otherwise how would you know what to connect to?) your local client can use a random port number from a large range, picked at random. The client needs this port so that the networking stack in your kernel knows where to send the replies from the remote web server.

Common Ports

There are literally thousands of known port numbers used by a whole variety of software suites, but there are just a handful you need to be aware of. I've listed them below.

| Port | Software/Use |

|---|---|

20 + 21 |

FTP (insecure protocol; don't use) |

22 |

Secure SHell (SSH) |

25 |

Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP); a.k.a the sending of email |

53 |

Domain Name System (DNS); but it's actually used via UDP mostly |

80 |

HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP); a.k.a "the web" |

110 |

Post Office Protocol v3 (POP3); a.k.a the receiving of email |

143 |

Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP); the receiving of email |

179 |

Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) |

389 |

Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) |

443 |

HTTP Secure; a.k.a "the web" but encrypted/secure |

587 |

SMTP over TLS/SSL; a.k.a the sending of email over encryption |

1433/1434 |

Microsoft SQL Server |

3306 |

MySQL database |

3389 |

Windows Terminal Server (RDP) |

5432 |

PostgreSQL database |

And so, so many more. Review the complete list over at Wikipedia.

Just remember that you're not expected to remember them all. I'd argue you only really need to recognise the important ports you're going to see daily as a working system administrator in a Cloud environment:

- HTTP on

80and HTTPS on443 - SSH on

22 - DNS on

53

And not so daily from an administrative perspective (or at all in some cases), but used heavy by everyone daily (minute by minute for some devices like mobile phones):

- SMTP on

25and587 - POP3 on

110 - IMAP on

143

Or put another way: email.

Special Ranges

There are some special port ranges you should be aware of, as well as some rules with regards to what ports can be used by a process.

Well known port numbers range between 0 all the way through to 1023. These are the port numbers used for the most common services we'll come to know and understand throughout this course. These port numbers include everything above under "Common Ports" until port 1433/1434, non-inclusive. These are also known as privileged ports, and root level (or Administrator on Windows) access is required to bind a process to these port numbers.

Ports 1024 to 49151 are considered "registered ports".

Ports 49151 to 65535 are called "dynamic ports".

Stateful

This is an important thing to remember about TCP connections: they're stateful. That means the connection as some state as it's operate on, such as ESTABLISHED, which is to mean the connection is open and ready to receive/send data to the user(s). The TCP connection can also be in a LISTEN state which means the connection is ready to receive new TCP connections, like from a web browser or another client. Then there's CLOSED which, of course, means the connection has no state and has in fact closed and a new connection must be established.

A TCP connection is almost like a pair of tin cans and a piece of string that run between the client and the server - it's persistent and repeatedly used to send data over time until someone cuts the wire and marks the connection as CLOSED.

It's because of this stateful nature that TCP is an "expensive" protocol. That means an active TCP connection uses a lot of system resources and network bandwidth to maintain itself and send data back and forth, between client and server. You do get a lot of functionality, reliability, error checking, etc. for the cost, but it's not the right protocol for all use cases.

When we look at UDP you'll discover why TCP isn't actually used for a lot of the Internet's most common services like DNS.

The Header

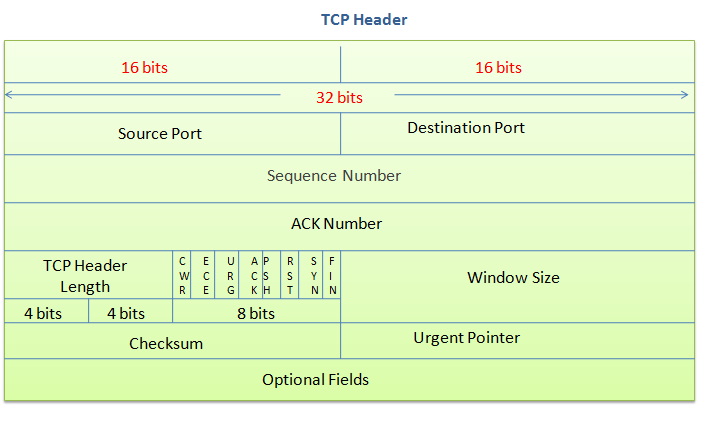

Now let's finally look at the TCP header. You don't need to memorise this or even study it in detail. In fact, let me give you a pro-tip here: I've never referred to this diagram or this information during my professional career, even during my brief one year as a network administrator.

Let's break down the important things you'll work with the most when configuring firewalls, software, and the likes.

Ports

We've looked at ports already. There are two ports mentioned in the header: source and destination.

From the client's perspective, the destination port is usually the port number of the remote service you're accessing like 443 for HTTPS or 22 for SSH. The source port is going to be a random port number in a very large range. This is used so that the remote end of the TCP connection can reply to the client, citing the source port as being the port to reply to.

From the server's perspective, the source port is the port the application is LISTEN-ing on via a TCP connection, like 443. The destination port is like the "reply to" port of the client connection, so when the server sends back information it "replies" to that source port.

These two port numbers are going to be the primary thing you'll be concerned with and even then you're not really going to be too concerned with the source port much.

Sequence and ACK Numbers

These are used by the TCP connection to check that packets are delivered as expected. When a packet is sent the sending party expects to see an ACK packet sent back to say, "I got that!" If it doesn't then the packet may be sent again.

You won't work with these values or parts of the header at all.

Everything else

All the other parts of the header have their place and function, of course, but you simply don't need to concern yourself with them at all. I don't believe I've ever had to be concerned with anything more than ports, perhaps the Windows Size and the state of the connection.

I'd recommend you leave studying the rest of the protocol's details until you need to know more.