Protocols

If computer networks are host hosts send data to each other, what language are the computers talking?

A protocol is a set of rules that defines how two computers talk to each other on the same network or between different networks. It's like a predefined language that the computers both talk which enables them to exchange information with each other. This is very similar to two people speaking English, German, or Finnish, except unlike natural language, a networking protocol is very strict in structure and you cannot make assumptions or "guess" what the other computer is trying to say based a rough understanding of the language - computers must speak the protocol precisely for it to work.

Most of the protocols you'll encounter operate in a client/server model, which means one side of the connection is a client requesting some data or information from the other side, the server. The client is like the host on your Local Area Network (LAN) and the server can be on the same host as you, a host on the same network as you (the LAN), or on an entirely different host on an entirely different network thousands of kilometres away.

An example...

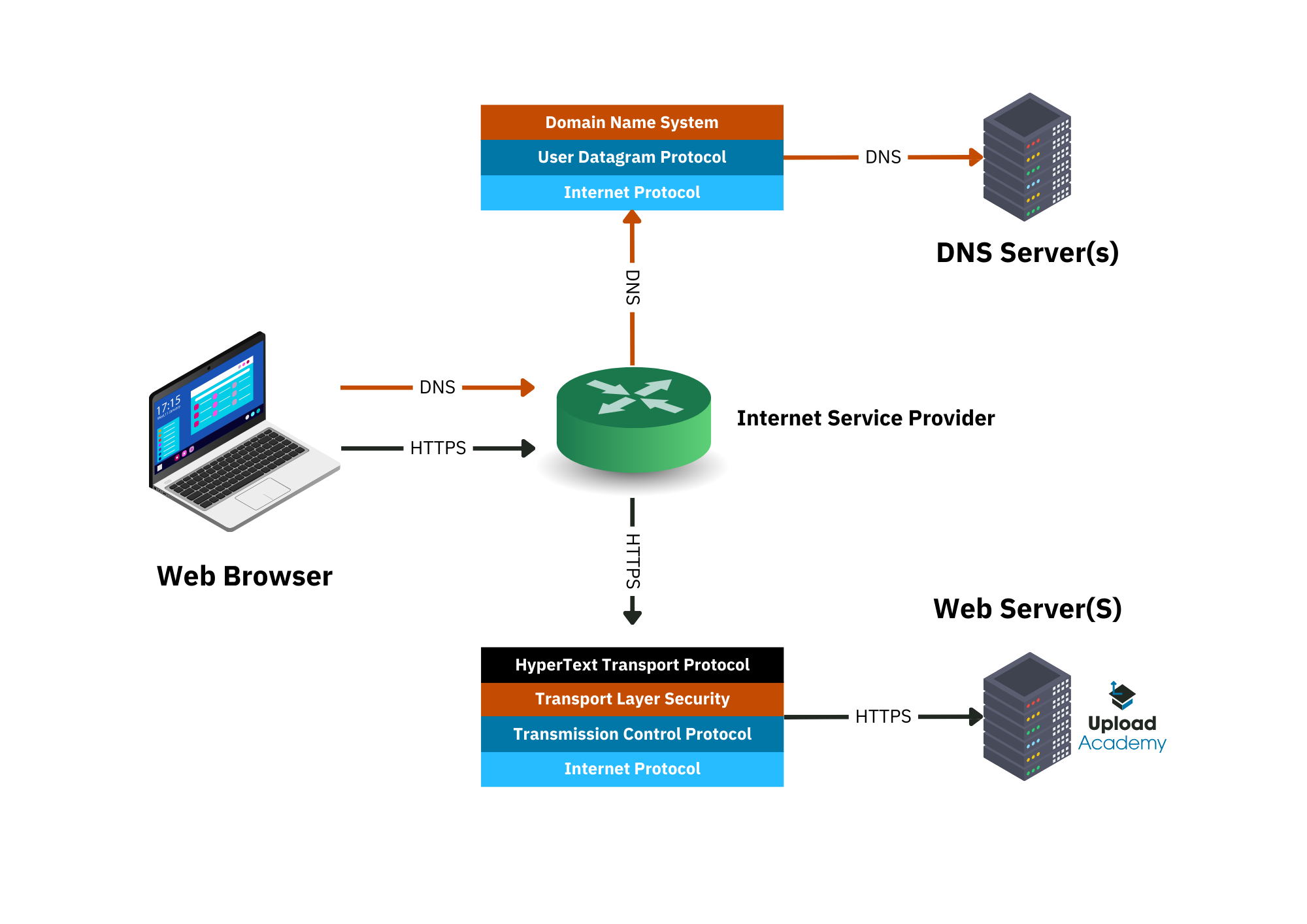

When you use your web browser, you're using several protocols to send requests. In the case of browsing the Internet the most common set of protocols are DNS, HTTP, TLS, TCP, UDP and IP. These protocols are used in combination with one another to exchange information between your browser (the client) and the web servers (the server) that host the websites you ask for.

We can visualise this easily enough by looking at an example. Below we have a visualisation showing two requests being made using the previously mentioned protocols: DNS, HTTP, TLS, TCP, UDP, and IP.

(We're not going into too much detail here, as we do that later on.)

On the left we have a "Web Browser". This is the client in the client/server model. In the bottom-right we have the "Web Server(s)" (there might be more than one serving the same website), which as the name implies is literally the server in the client/server model. The client asks the server for something, and in this case it's a website.

How is the website requested and how is it delivered? Let's break down two of the key protocols in this example: DNS and HTTP.

DNS

Before you can send a request for the website you want, your browser has to use DNS so that it can translate upload.academy into its IP address, such as 1.2.3.4 (that's not the real IP for upload.academy, it's just an example.) DNS is how we're able to use human readable names for our websites, like upload.academy or duckduckgo.com, and not 67.78.89.12 or 123.45.67.67 (or whatever.) We don't remember numbers like that very well, especially when you consider the amount of websites and services we now all use on a daily basis.

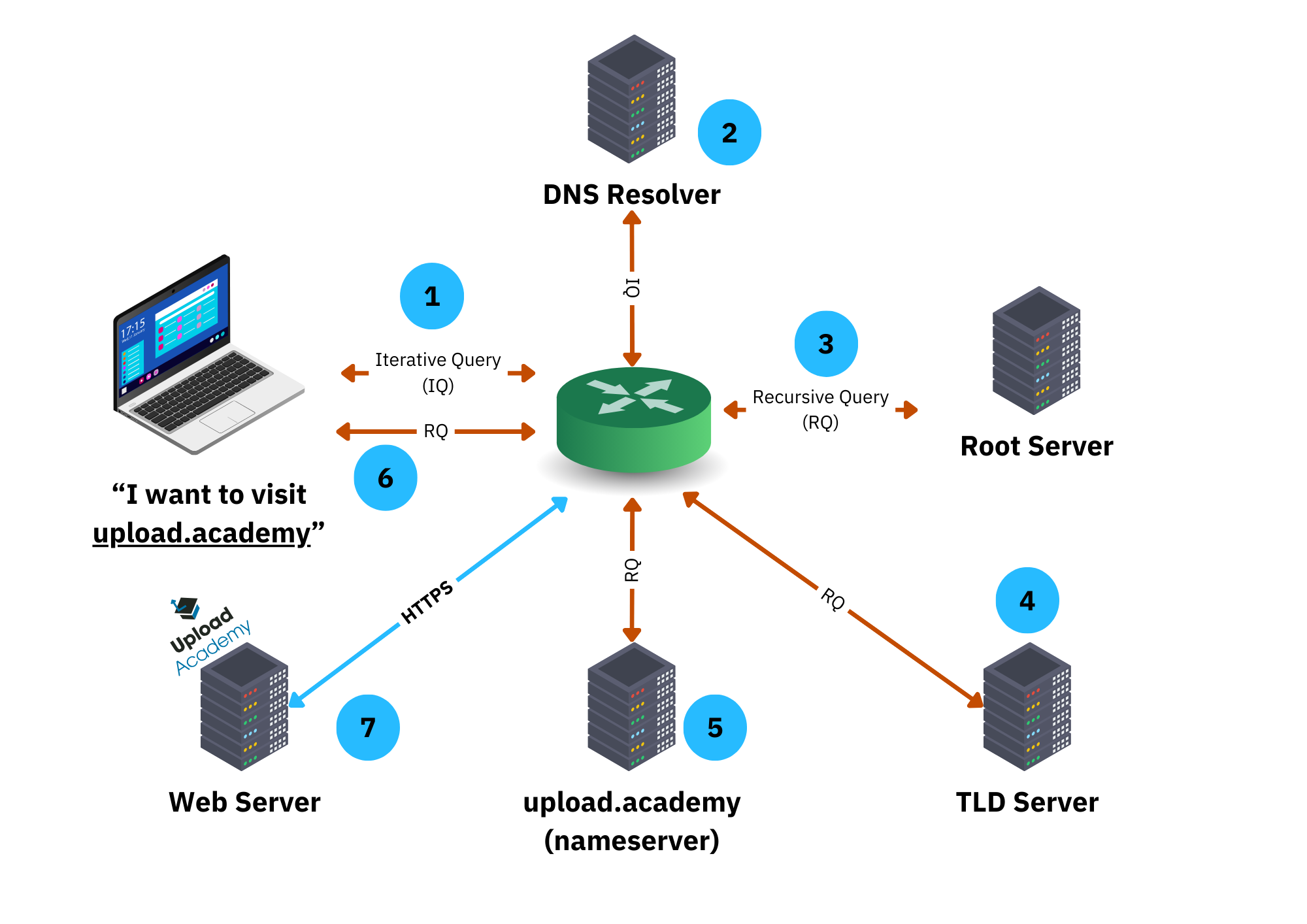

Let's visualise a DNS request and then break it down into its steps:

Breaking this down, we have:

- You make a DNS request to resolve

upload.academy.(note the.at the right-hand-side [RHS]); - The response from the DNS Resolver points to the Root Server;

- Your local system performs an "Iterative Query" (IQ) against a Recursive Resolver;

- The DNS Resolver looks at its cache first, then forwards the query to the Root Server for:

.(RHS) - The response from the Root Server is forwarded to the TLD Server for

academy. - The response from the TLD Server is used to then get us the Authoritative Nameserver for the

.upload.part of the domain - Finally we're given the IP address(es) of the Upload Academy web servers

That's a lot of steps! The key thing to remember is the DNS system allows us to define human-readable addresses like duckduckgo.com, which we can easily share with each other using natural human languages, but in turn allow the computer to lookup and translate the human-readable address into a more computer friendly format: the IP address!

We'll look at IP addressing shortly.

Caching

That seems like a lot of steps to complete every time you want to visit a website, and that's why the DNS Resolver has an internal cache: it will store results it has previously collected, like upload.academy = 1.2.3.4, allowing future requests for the same information to be significantly faster. This eases the load on the global DNS system and it makes things faster for you as the user.

How long items stay in the cache depends on how the Resolver was coded. It could have been coded to cache the results forever, which would be silly. It could have its own "timeout" - a period of time it considers sensible before going back to the Root Server and getting a potentially updated value. Finally, it could simply honour what's known as the Time To Live (TTL) value on each DNS record. This value tells DNS caches how long to cache the record for before going back to the network for the potentially updated value.

DNS Summary

DNS is a critical tool which makes the Internet a much easier place to navigate. It can also be a burden from a system's administration perspective and you might hear people saying, "It's always DNS!" because more often than not, it is!

We look at DNS in more detail further into the course.

HTTP

After you've looked up the IP address using a DNS request, your browser is now ready to request the actual website itself.

Websites are served on the back of the HyperText Transport Protocol (HTTP), which is a protocol you're using right now to read this course. Like other protocols, including DNS above, HTTP has a system of rules that define how software "talks" to other software in the HTTP "language". Your browser "spoke" HTTP to the Upload Academy web server, which understands and also "speaks" HTTP. That enabled everything to work as expected:

- You request

upload.academy - You got the website

We've already visualised HTTP at a high level at the top of this page, so instead let's now follow a very deep, raw HTTP request.

A Technical Example

We can actually look at an example of "talking" HTTP to a remote web server. Don't worry about understanding everything right now. Just remember that you're looking at an example of a conversation between my local computer and the remote server(s) that is google.com.

I'm going to use my local terminal to run the command nc followed by some HTTP commands after that. This is me connecting to google.com:

The nc command line tool is known as netcat. I'm giving it two parameters: google.com and 80. That means I want to connect to google.com and I want to connect to it on port 80 (more on ports later.) The name google.com would need to be resolved to an IP address, which is handled automatically for me by my computer and its software.

After that connection is made I start "talking" HTTP (version 1.0) to the server, by typing literally this into the terminal:

Here I'm using the HTTP "verb" GET, which means I want to get something from the remote server. I'm continuing the conversation with three additional pieces of grammar:

We'll cover these kinds of headers when we look at HTTP in detail later on. For now just understand I'm using the HTTP language to "talk" to the remote server at google.com on port 80.

After I press return (enter) a few times the server talks HTTP back to me:

Here we have HTTP headers and a body. The response from the server is HTTP/1.0 301 which means the resource I requested (/search?q=hello) isn't available at that location and I need to go elsewhere. So it's not happy with my request but in short google.com replied saying:

Which are the important parts of this conversation and they mean: send the request to http://www.google.com/search?q=hello instead. Even though the conversation didn't get me the (search) results I wanted I was successful at talking HTTP to a remote web server, and that's all we're demonstrating here.

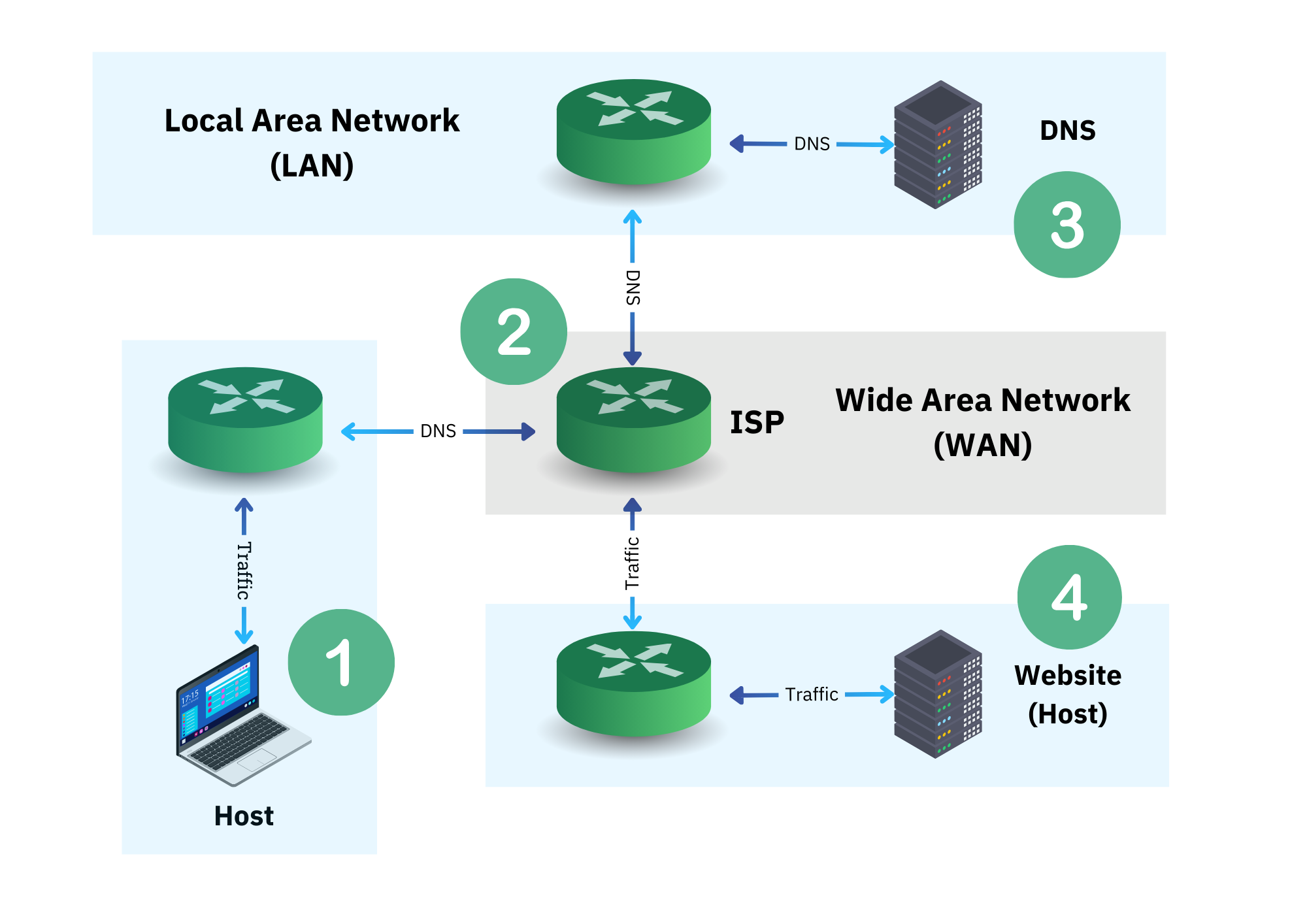

Visually, this conversation looks like this:

Broken down we have:

- We send the

HTTP/1.0 GETtogoogle.com; - We go from our LAN to the WAN, and then eventually to some LAN inside of Google's (vast) infrastructure;

- A DNS request is made to the DNS infrastructure;

- We use the address given to use to make a connection to Google's server.

Summary

And that's what a computer/networking protocol looks like. Essentially it's a strictly defined language and set of rules for establishing a channel of communication and then transmitting information over that channel between two or more hosts on one or more networks.

Next

Now let's look at networking models, which help us understand even more how all of this comes together.